Dr. Lisa Gilbert, a Social Studies teacher in St. Louis, Missouri, recently tweeted about her experience with her 8th grade class transcribing and examining some of the BPL’s anti-slavery manuscripts. She blogs about it here...

As a social studies teacher, I hope for my students to develop an appreciation of the discipline of history itself. Rather than emphasizing memorization of dates and names – the kind of things that fall out of our memory as soon as we put them down on the test – my goals include exposing students to the intricacies of professional work done by historians.

Recently, my 8th grade Ancient World History students were reading John H. Arnold’s History: A Very Short Introduction. In chapter four, Voices and Silences, Arnold describes the process of working with sources. He notes that historians need the ability to decipher handwriting and spelling that can vary widely across time periods.

I wanted to give my students a concrete experience of what this meant, and the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts project at Zooniverse gave us the perfect opportunity. Knowing the logistics would be simpler if I used my Zooniverse account to centralize our class submissions, I selected a document and used screenshots to assign each student a series of lines for homework.

When students brought their initial attempts to class the next day, we had a good laugh over how nonsensical some of their results were:

But then, working together as a team, we redoubled our efforts. One student cheered out loud when she realized this set of three markings spelled out the word ‘embellishments’:

Another student was positively indignant to learn that the sharp S could be used in English and therefore the following word read “expressed”:

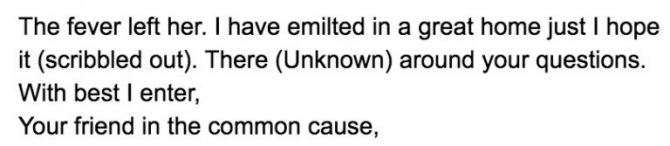

We agonized over each line, but eventually prevailed. Once we had compiled and submitted a full transcription, we turned to investigate the document itself. We took our inspiration from our continued reading of Arnold’s History: A Very Short Introduction, in which he narrates a historical investigation of an archival document. We generated a list of what we wondered about while we read, noting that these were the kind of things that could develop into questions for historical inquiry:

My 8th graders brainstormed questions about the document we transcribed for the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts project. How could we track down people and documents hinted at in the text? What did it say about women’s roles? What is said (and unsaid) about race?

My 8th graders brainstormed questions about the document we transcribed for the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts project. How could we track down people and documents hinted at in the text? What did it say about women’s roles? What is said (and unsaid) about race?

Having identified these questions, we set about searching for additional information that could help us answer them. This included viewing other documents by Anne Warren Weston on Digital Commonwealth and learning of the existence of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. From there, we used some of our research skills learned during our National History Day projects to look at secondary literature, for example finding Debra Gold Hansen’s Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women’s Political Culture in Antebellum America.

Our goal was not to come to any definitive conclusions about the manuscript. Having read Arnold’s estimation in History: A Very Short Introduction that “The process of creating a story is not simply that of placing one brick upon another, until a structure arises; it involves deciding the causes and effects of the things described, negotiating what has already been said by other historians, and arguing for what the story means” (p. 81), we knew this was a bigger project than we could reasonably approach.

Our real accomplishment was that we became more aware of just how many questions we could ask about a single document, and how many paths sprung forward from the questions we asked. Further, we became more aware of the work of archivists in preserving these materials and making them accessible.

Being able to participate in the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts project for the Boston Public Library added meaning to our investigation of the work of historians. While we could have transcribed anything, my middle school students found it motivational to know that their Zooniverse transcriptions would make a tangible contribution to the work of real historians.

Of course, documents from 19th-century America are a far cry from the primary sources my Ancient History students typically encountered in my class. But those sources would have required us to learn both language and letters (imagine being given a tablet in Phoenician as homework in the 8th grade!). Further, the fact that these manuscripts testified to the persistence of abolitionism in American history was, in my mind, a bonus. Having worked so hard to decipher these words, their meaning was more deeply engraved on my students’ hearts: it would be much harder, from here on out, to believe that slavery was “just something people thought differently about back then.” Instead, my students know that resistance has long been a part of American society – a worthy lesson to glean from a document that we initially believed so hard to understand.

Dr. Lisa Gilbert (@gilbertlisak)

Instructor in Social Studies

Thomas Jefferson School (St. Louis, MO)

Add a comment to: 8th graders in Missouri transcribe anti-slavery documents and learn about the abolitionist movement