If you help transcribe abolitionist letters at the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts Project, you will come across a few letters that are printed on interesting stationery. Some abolitionists wrote their personal letters on letterhead with anti-slavery drawings. Sometimes, they used this stationery strategically when writing to individuals who held opposing views on emancipation.

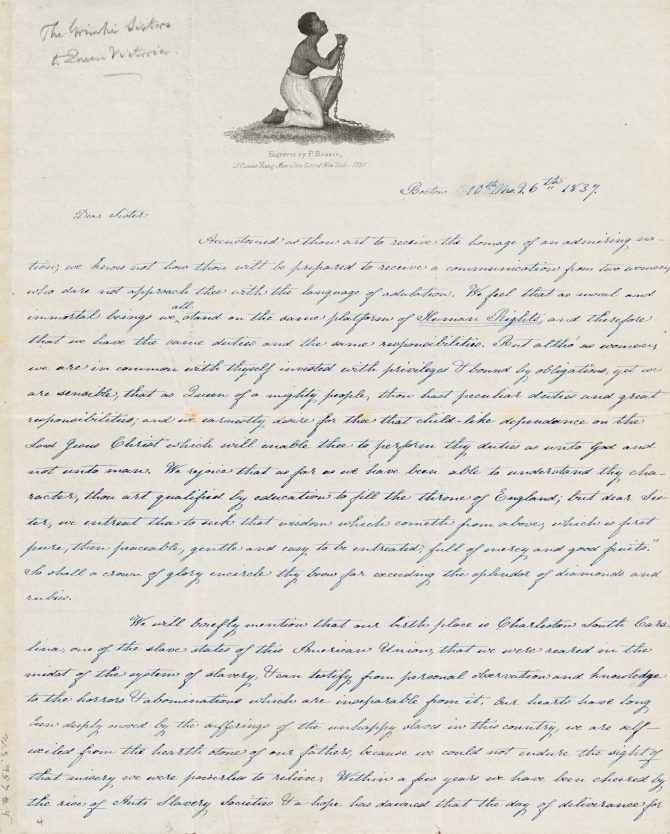

In a letter to the Queen of England, Sarah Grimké and her sister, Angelina Grimké, asked Queen Victoria to stop the apprentice system in the British West Indies. Great Britain had started the apprentice system in 1833 as a halfway policy, in which slaves first became apprentices before they could gain their freedom. The Grimké sisters supported immediate emancipation, and they argued that the policy caused great suffering for slaves, who continued to work under the same master. The sisters appealed to Queen Victoria as a woman, praising her speech to Parliament at a time when women were criticized for speaking publicly, as it was “inconsistent with the modesty of woman.” Strategically, the Grimké sisters wrote on stationery with an illustration of a kneeling female slave. In this way, they suggested that the enslaved woman, the sisters, and the queen shared one common identity as women despite their different ranks.

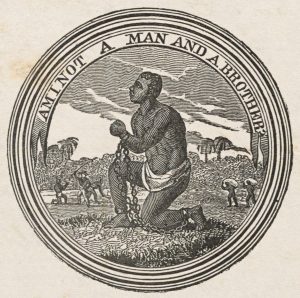

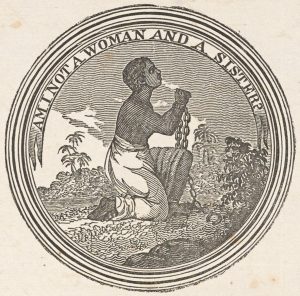

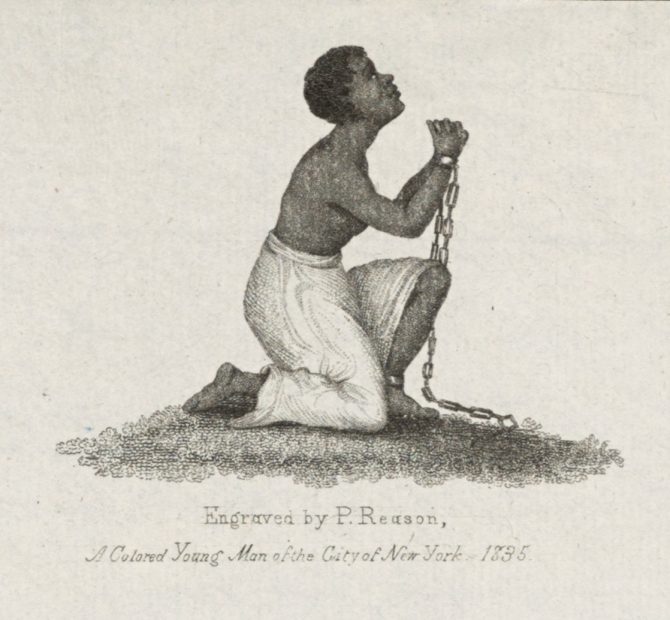

The kneeling slave appeared often in abolitionist literature. Before it was a female slave, it was a male slave, as seen in a letter from Nathaniel Rogers to William Lloyd Garrison. The man asks, “Am I not a Man and a Brother?” Another version of the kneeling woman on a different letter similarly asks, “Am I not a Woman and a Sister?” Notably, the kneeling woman on the queen’s letter does not include the printed question, because it is implied. The kneeling slave was such a common abolitionist image that everyone, including the queen, would have recognized the picture and remembered the unwritten question.

Patrick Henry Reason, an African-American engraver, drew the version of the kneeling woman that appeared on the queen’s letter. Born a free man, Reason ran a printmaking business in New York City, where he engraved drawings for books and journals. Unlike previous versions of the kneeling slave, Reason adds more detail and individuality in the face of the woman. She appears, not as a type, but as a portrait of a real person. In this way, the picture effectively showed her humanity. This forced the viewer to consider the injustice of her bondage and the immorality of slavery.

In 1838, Great Britain abolished the apprentice system in the British West Indies. Thousands of British women signed a petition opposing the system, and public opinion turned against the policy. The emancipation of slaves in the Caribbean was due in large part to the efforts of the transatlantic anti-slavery movement. It would take an additional twenty-five years before slaves saw freedom in the American South.

Kelsey Gustin, the author of this post, is a Humanities PhD intern at the Boston Public Library and a doctoral student at Boston University in the History of Art and Architecture. She specializes in nineteenth and twentieth-century American art and is presently writing her dissertation on representations of working-class immigrants in New York City from 1890 to 1920.

Kelsey Gustin, the author of this post, is a Humanities PhD intern at the Boston Public Library and a doctoral student at Boston University in the History of Art and Architecture. She specializes in nineteenth and twentieth-century American art and is presently writing her dissertation on representations of working-class immigrants in New York City from 1890 to 1920.

Add a comment to: Abolitionist Stationery