Like many parts of the world, Massachusetts has had a complicated relationship with its feline residents. This is especially true of those that are free-roaming, stray, or feral.

Cats' innate tendency to prey on small animals has resulted in a complicated problem: how do we balance protection of wild creatures against the lives and welfare of cats? After all, they are hunters by nature, not by malice, and we are in some sense responsible for their presence and deeds.

Below are some episodes from the cat-lore of the Commonwealth, showing just how long this problem has puzzled our people. This long-running conflict between cats and conservation might help us to think more carefully about how we ascribe value to nonhuman lives.

Concern (or Not) for the Cats of Massachusetts

In the early days of movements for animal welfare, cats were, as historian Janet M. Davis notes, "conspicuously absent as a subject of sustained programmatic concern" (1). But in Boston, at least, real concern was shown for felines in the Back Bay; left behind as their wealthy owners departed for summer vacations.

A Globe report from July of 1903 reports that "the Back Bay police have been told by their superior officers not to allow a cat to go hungry, and to see that they are properly cared for while the houses where they belong are closed for the season" (2). There was real concern here, but not everyone loved cats. As Davis notes, "perhaps most damningly of all, cats preyed on beloved songbirds." It was this tendency that was to be the cat's capital offense in the eyes of the developing environmentally concerned community of Massachusetts (3).

"Destroyer of Wild Life"

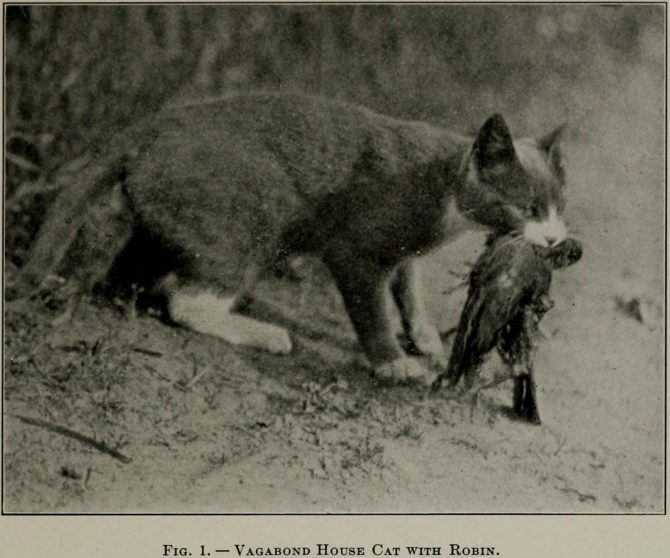

As early as 1908, State Ornithologist Edward Howe Forbush was sounding the alarm about the threat cats posed to the indigenous birds of the Commonwealth (4). In 1916 he published, through the State Board of Agriculture, his anti-feline magnum opus: The Domestic Cat: Bird Killer, Mouser and Destroyer of Wild Life: Means of Utilizing and Controlling It.

The work was created primarily from anecdotal evidence drawn from across the Commonwealth. It painted a picture of the cat as an irredeemable predator of helplessly vulnerable birds. This characterization was echoed by Bradford Scudder, Secretary of the Massachusetts Fish & Game Protective Association. His 1916 Conservation of Our Wild Birds placed cats at the "head of the list" of enemies of wild birds, deserving to be "killed on sight." This perspective soon found its example in the plight of a dwindling ground-dwelling bird reduced to living nowhere else but Massachusetts.

Exit the Heath Hen

By 1925, only 3-25 heath hens remained on Martha's Vineyard (5). This subspecies of the greater prairie chicken had once ranged throughout the eastern United States. But, overhunting and habitat destruction had driven it to near-extinction and isolated it on this iconic Massachusetts island.

Feral house cats were vilified as the heath hen's greatest threat throughout the 1920s, and lethal measures were undertaken to secure the doomed population, as the image at right attests.

The last heath hen, dubbed "Booming Ben" for the noise he made in a futile attempt to attract mates that no longer existed, died in 1932. However, both contemporary scientific accounts (6) and modern reviews (7) attribute the extinction of the subspecies to rapacious human activity rather than to the cats who were popularly vilified and made to pay the ultimate price at the time.

The Great Provincetown Roundup

The complicated relationship between human beings, cats, and indigenous wild creatures is perhaps nowhere better demonstrated than in 1930s Provincetown on Cape Cod.

Stray or feral cats were considered an issue of public concern there as early as 1930; cats abandoned by the summer population were being regularly shot (8). And in 1933 the Globe revealed that the Great Depression was impacting not only humans, but also dogs and cats, driving many into homelessness (9). It was a telling recognition of the inextricable links between human affairs and the lives of other animals

By 1937, the cats found a human advocate in Mrs. Martha J. Atkins. Her opposition to the latest shooting campaign yielded the dubious solution of trapping cats for euthanasia by other means.

Even under the new plan, Atkins was relentless, closely observing the proceedings to ensure that the trapping and containment was conducted in as humane a manner as was possible given the circumstances.

'Old Sharktooth'

The Provincetown affair also saw the entry into the historical record of one especially remarkable feline. Dubbed 'Old Sharktooth,' the cat's "wily, elusive ability to escape capture and subsequent execution" earned him or her exclusive coverage in the Globe (10). This cat was renowned for his/her propensity to eat clams by cracking the shells with ease, and to enjoy the bait set in the wire cat traps before s/he would "gnaw its [sic] way to freedom."

No human record has yet been found of Old Sharktooth's ultimate fate. Regardless, this cat serves as a reminder of the individuality and unique experience of every nonhuman creature. This uniqueness is often overlooked or omitted in human accounts of the past (and present). In future entries in this blog, we'll look more closely at animal history and at works that recognize and honor the individuality of nonhuman animals and the singularity of their experiences.

An Endless Struggle

The debate over the management and fate of stray and feral cats continues today, with the sides generally polarized between advocates of lethal management (i.e. killing) and trap-neuter-return (TNR) programs. TNR programs allow free-ranging cats to preserve their lives while preventing the proliferation of further cats. To learn more about the state of the debate, check out the following BPL and freely available resources:

A Balanced Debate

Anti-TNR Polemics

Positive Accounts of TNR in Massachusetts

- "Innovative Program Manages Massachusetts Cat Population" - a Northampton Community Television program on the Internet Archive

- Spehar, D.D.; Wolf, P.J. "An Examination of an Iconic Trap-Neuter-Return Program: The Newburyport, Massachusetts Case Study." Animals 2017, 7, 81.

And finally...

The marginally relevant but delightful Kedi, about the semi-feral cats of Istanbul, is available to stream on Kanopy:

Notes

- Davis, Janet M. (2016). The Gospel of Kindness: Animal Welfare and the Making of Modern America. New York: Oxford University Press, 12.

- "Caring for Pussy: Police on the Lookout for Stray Tabbies." Boston Globe, 26 July 1903, p. 20.

- Davis (2016), 12.

- "For and Against Cats." Boston Globe, 10 July 1908, p. 6.

- "Start Fight to Save a Few Heath Hens." Boston Globe, 15 June 1925, p. A12.

- "The Last Heath Hen," The Scientific Monthly 32 (4) (April 1931), 382-384. Freely accessible via JSTOR.

- Heisman, Rebecca (2016). "The Sad Story of Booming Ben, Last of the Heath Hens." JSTOR Daily.

- "Provincetown Cat and Bird Lovers at Odds." Boston Globe, 7 March 1930, p. 17.

- "Even Ranks of Homeless Cats and Dogs Increased by Slump." Boston Globe, 15 February 1933, p. 8.

- "'Old Sharktooth' Main Objective Of New Cape War on Stray Cats." Boston Globe, 25 October 1937, p. 2.

Add a comment to: Cats and Conservation in the Commonwealth