A guest blog post by Christina Manzo, Digital Projects Intern.

“I pay very little regard to what any young person says on the subject of marriage. If they profess a disinclination for it, I only set it down that they have not yet seen the right person.”

–Jane Austen, Mansfield Park

Given my relative youth, it’s a wonder that I would even think about writing a blog post about marriage. Luckily for me, I don’t want to talk about the institution of marriage as much as the significance of the historical process.

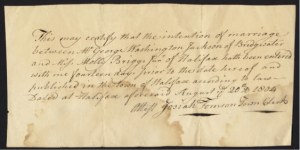

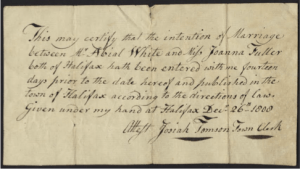

Recently, the Boston Public Library’s digitization team brought in a group of handwritten 18th and 19th century marriage intention certificates from the Holmes Public Library in Halifax, MA. These documents are part of the town’s Congregational Church records.

Recently, the Boston Public Library’s digitization team brought in a group of handwritten 18th and 19th century marriage intention certificates from the Holmes Public Library in Halifax, MA. These documents are part of the town’s Congregational Church records.

As I have always held some level of fascination concerning this particular period, these documents immediately piqued my interest. Historically, the requirement of an intention of marriage has been an incredibly restrictive one.

During this time period, the act of marriage was not seen as a pact between two people as much as it was seen as the responsibility of the entire surrounding town. To ensure that the entire town or village approved of the match, the intention of marriage had to be filed. Typically, these forms would include names, counties of origin, the professions of the brides and grooms, the dates on which the forms were filed, and official signatures.

This intention was then printed and distributed throughout the town as a flier that would be hung on post offices, schools, general stores, etc. The marriage then had to be announced in church on three consecutive Sundays or Holy Days, which would give the townsfolk the opportunity to object to the marriage. This was referred to as ‘Crying the Banns,’ which still occurs for couples intending to marry within the Church of England. It ended many couples impending nuptials, especially in the case of a discrepancy in class or social standing. Laws such as The Marriage Act of 1753, made it almost impossible for couples to bridge the social gap between their two classes. As a result, many weddings blossomed not out of love and respect, but out of the security of knowing that your match would not be rejected.

During this time period, many women lamented the matrimonial process, including such famous people as Mary Darby Robinson and Jane Austen. Robinson accounts her own doomed marriage in her posthumous memoir published in 1801.

During this time period, many women lamented the matrimonial process, including such famous people as Mary Darby Robinson and Jane Austen. Robinson accounts her own doomed marriage in her posthumous memoir published in 1801.

“Such was my dislike to the idea of a matrimonial alliance that the only circumstance which induced me to marry was that of being still permitted to reside with my mother, and to live separated, at least for some time, from my husband.”

As I glanced through the Halifax records I couldn’t help but wonder how many of these women suffered the same fate as Mary Robinson? Did these people really love each other? Were these simply marriages of convenience? Did some of these couples even make it to the altar?

It made me think about how lucky I am to live where and when I do. To be able to choose my own path, whether that includes marriage or not, is a freedom that young people don’t really think about too often. I think it’s mainly because we see ourselves as so far removed from our oppressive past that it doesn’t seem possible that this kind of emotional tyranny would exist today. This part of our history deserves to be remembered, however, if for no other reason than to remind us of our own cultural evolution. The preservation and study of the past is significant because, as Albert Einstein once said, “The distinction between the past, present, and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

Add a comment to: Digitizing the Banns