Content Warning: Some images and content in this post contain depictions of the slaughter of animals

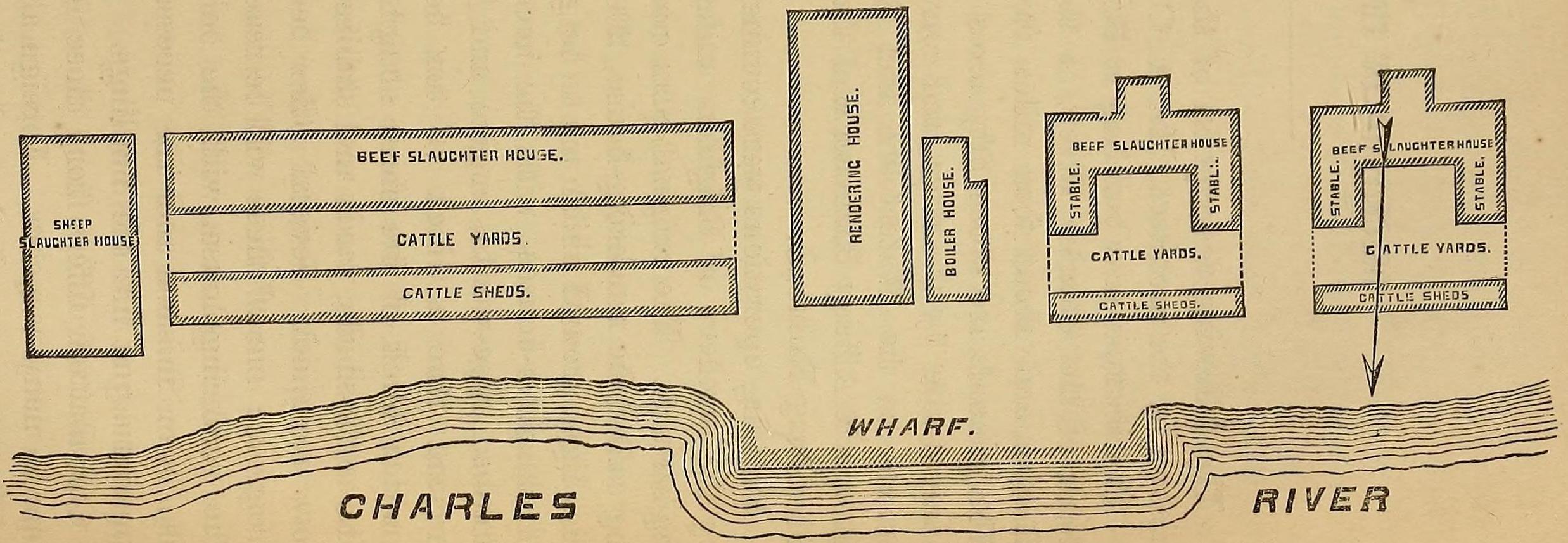

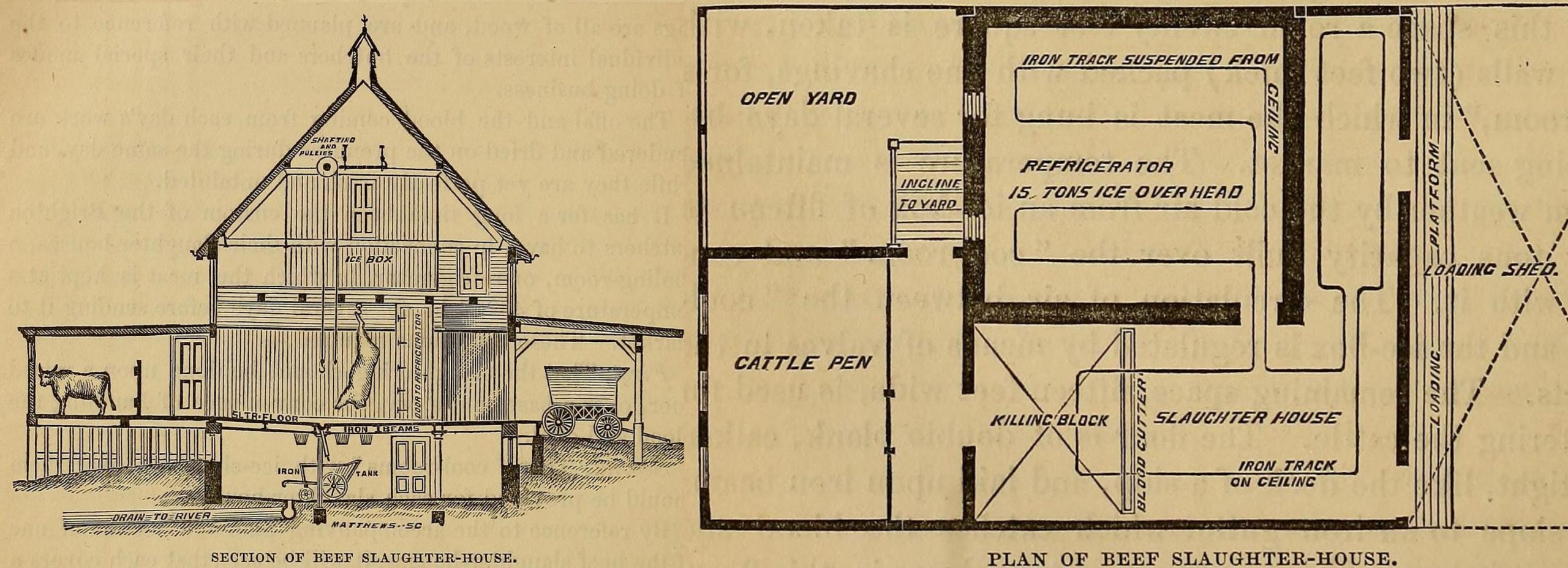

If animals survived the grueling journey to the Brighton abattoir complex (see Part I), and didn't escape and get shot to death (see Part II), they would find themselves in holding pens awaiting slaughter. In 1874 the complex included four slaughter facilities for cows and one for sheep. These were state-of-the-art at the time of their construction, with corpses hung along a rail and stored beneath a massive ice block to keep them cold.

In its early years, the abattoir complex slaughtered about 400,000 animals every year. Of these, about 67,000 were cows and steers, about 323,000 were sheep, and about 10,000 were calves.

Later in the 19th century, refrigerated rail cars allowed cow meat to be shipped east from places like Chicago. As a result, the need to slaughter live animals in Brighton declined continuously. By 1902 only about 30,000 cows and steers and about 100,000 sheep were being slaughtered each year at the complex.

These may sound like big numbers, but remember that according to the US Department of Agriculture, in 2019 the US slaughtered about 33.6 million cows, 609,000 calves, 130 million pigs, 2.4 million sheep, 227.6 million turkeys, and 9.3 billion (yes, billion) chickens.

Filth and Fury

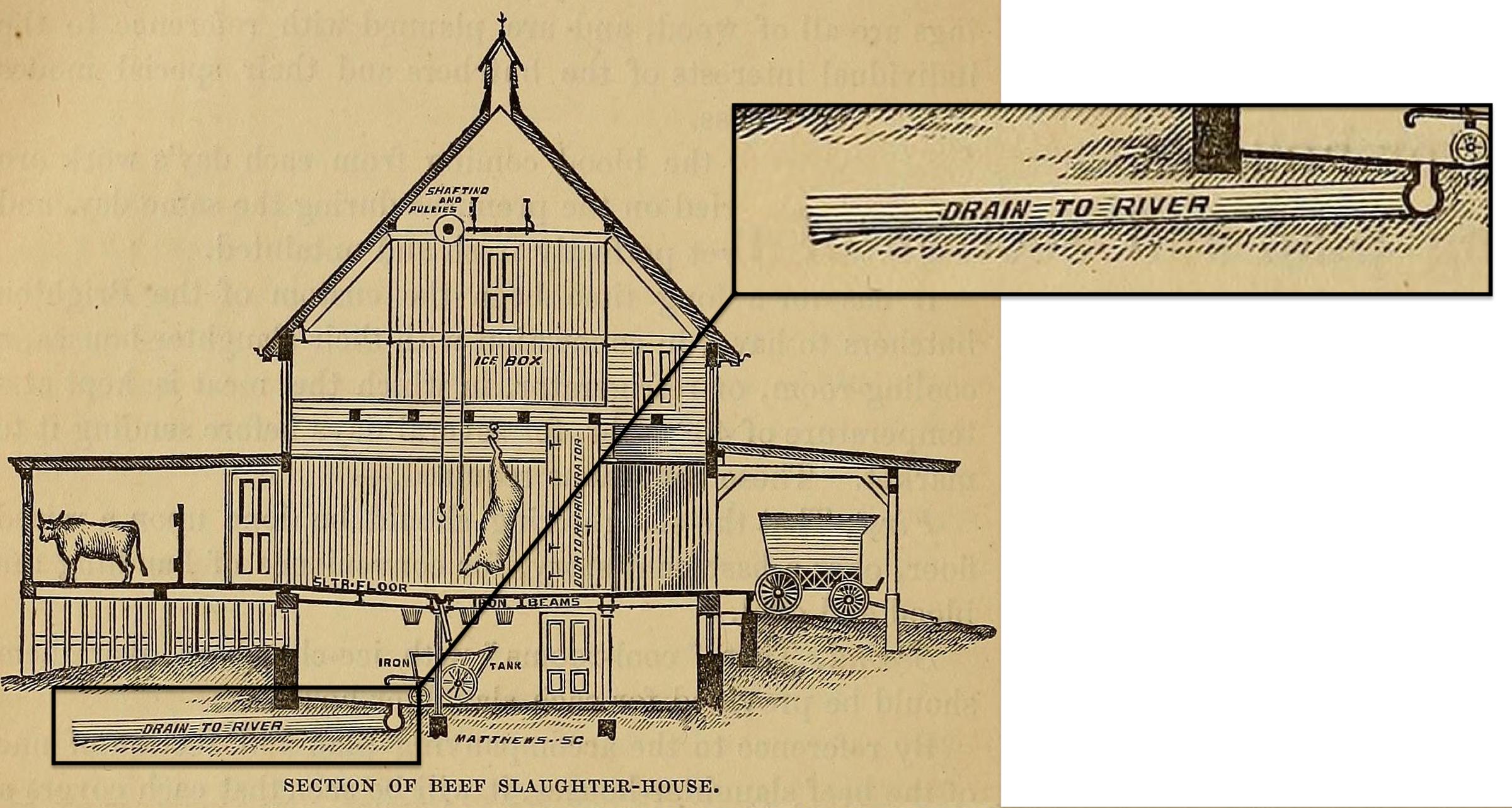

As time passed, it became increasingly clear that the Brighton abattoir represented a real threat to the health and environment of the surrounding area. To understand why, let's take another look at the lower-left corner of that cross-section of the slaughterhouse:

As blood and other animal waste products came down the 'blood gutter' from the slaughter floor, they were supposed to be collected in tanks to go to the rendering house. Anything that didn't get collected would drain directly into the Charles River, conveniently located adjacent to the abattoir complex.

Pretty soon this made people angry. In 1892 a Dr. Wolcott from the State Board of Health called the pervasive smell of putrefying blood "inexpressibly offensive." He also blamed the abattoir for "'a large proportion of the filth that is so pervasive in the Charles river.'" The next year, the Board of Health demanded that the abattoir "send no sewage into the Charles."

The complex and its operators had a troubled relationship with sanitation. The abattoir was finally declared 'satisfactory' in its sanitation in 1907, after years of operating subpar. But just two years later the facility came under investigation when meat that had been condemned as unfit for consumption was absconded with and, presumably, sold to unwitting consumers.

And in 1946, Mayor Curley had to issue 'commands' to the abattoir complex to 'deodorize' for the sake of the residents of Brighton.

The End...?

By the late 1950s, the Metropolitan District Commission effectively took over the land on which the abattoir complex sat. The slaughtering facilities were shut down, what became Soldiers Field Road and I-93 were routed through parts of the land, and the rest was developed into an 'industrial park'.

Today, industrial slaughter takes place far from Boston. The health and environmental impacts that are still generated by the raising and killing of animals for food are borne by faraway people (unless you count rising sea levels). And we certainly never have to deal with steers stampeding through the streets.

To learn more about animal slaughter, the meat industry, and their histories and impacts in the United States, take a look at some of the titles below from the BPL's collections.

And for a look at the individual potential of domestic food animals when given the chance for a 'natural' life, take a look at Allowed to Grow Old:

Add a comment to: ‘Inexpressibly Offensive:’ The Brighton Abattoir, Part III