John Singer Sargent’s epic mural cycle, the Triumph of Religion, adorns the walls of the third floor of the McKim Building at the Boston Public Library. The enormously ambitious project involved much preparation on the part of Sargent, who executed the paintings in his London studio and accompanied them to Boston to oversee their installation. These newly digitized sketches for the mural were a vital part of the preparatory work.

Sargent had begun conceiving of the murals in 1890, brought into the project by architect Charles Follen McKim. In a series of installations from 1895 to 1919, Sargent produced nineteen panels depicting key moments in the history of early Egyptian and Assyrian belief system, Judaism, and Christianity.

Sargent was a prolific artist, producing over 900 paintings and nearly 2,000 watercolors in addition to studies and sketches. His sketches capture the essence of his subjects with swift, confident lines and reveal his skill in capturing light, form, and expression in a few deft strokes.

The Arts Department’s collection of sketches for Triumph of Religion reveal Sargent’s hand at work, and are almost balletic in the way partial forms overlap, with limbs folding in and out of the page as he determined the positioning of the figures. In some sketches, Sargent retained the figure’s pose in the final panel, while other sketches are more experimental drafts, bearing only the slightest relation to the finished work you can see on the walls today. Examining these sketches against their final counterparts shows Sargent’s decision-making process in the development of the Triumph of Religion cycle.

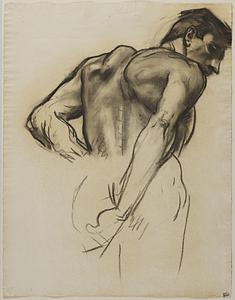

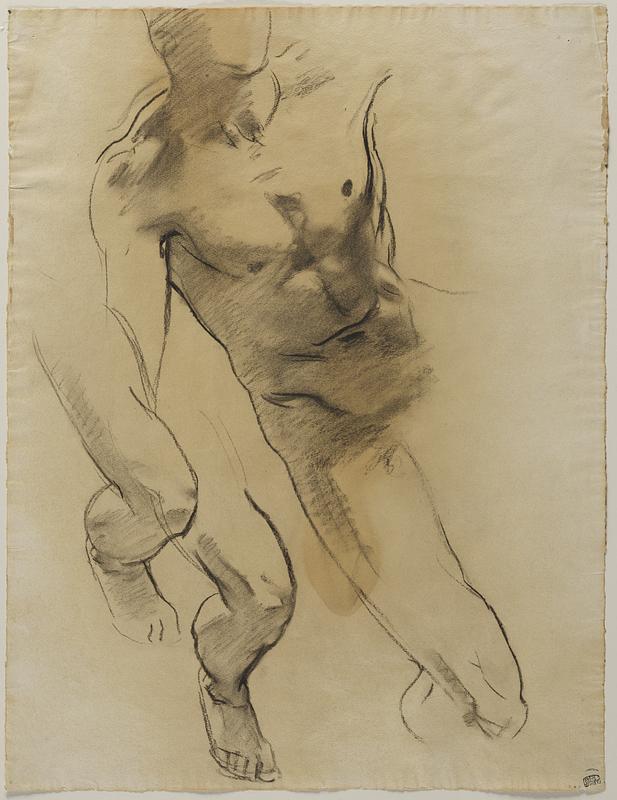

The Judgment panel depicts the weighing of souls at the gates of Heaven and their entry to either Heaven or Hell. In Sargent’s sketch of arms, for the angelic figure blowing a horn in the foreground, you can see the muscles are more clearly defined in the sketch than they are in the final painting, and reveal Sargent's academic training. The deep shading and bulging physique of the second sketch for the demonic monster in the background more closely matches the final painting.

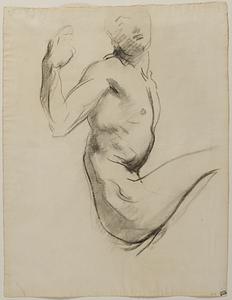

This is a study for the golden figure in high relief holding the chalice to Jesus’ blood from his wounds. This sketch is more complete than most, as Sargent neatly outlines a full figure, including a suggestion of a face, with only a few scribbles and some judicious shading.

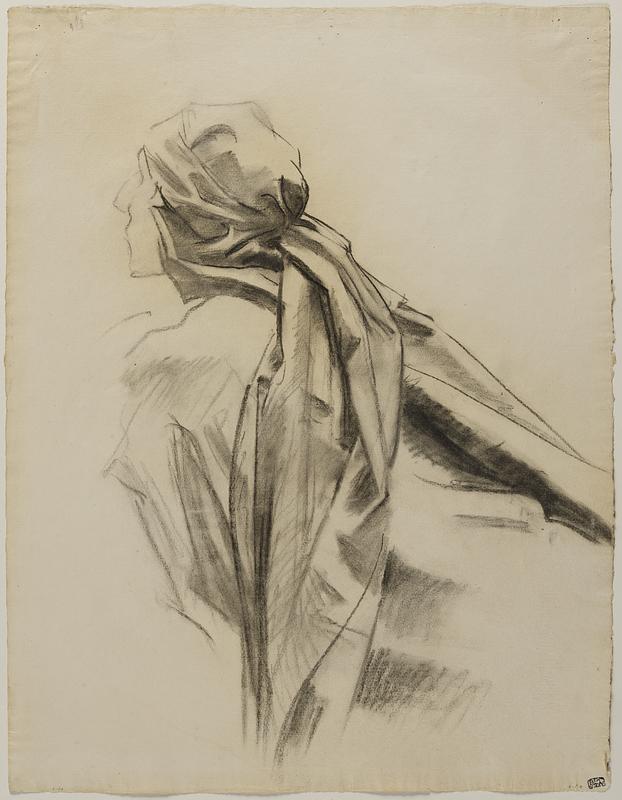

The Frieze of Angels, eight figures, represents Regeneration and the Resurrection as Christ rose on the third day. The angels align the bottom, holding symbols of the Passion of Christ: the spear, pincers, hammer, nails, pillar, scourge, reed, sponge, and crown of thorns. In this instance, the angel figure holds a flagellum, or whip, similar to a cat o’ nine tails and made of leather thongs embedded with sharp pieces of bone and metal to inflict maximum suffering. The figure in Sargent’s sketch holds these instruments of torture, very loosely defined, while his focus on the draping of the figure’s robe reveals his interest and skill in depicting folded and rumpled layers of cloth.

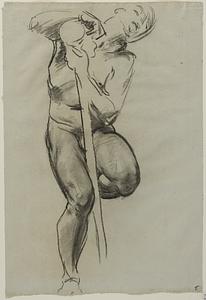

In this idealistic scene, the Messiah, pictured as a young man at center, proceeds through golden doors into paradise. The lush scene includes garlands of vines and pomegranates, and a lamb, wolf, and lion represent prophecies of Isaiah. Here, you can see very little relation between the sketch and the final work, as it appears Sargent was plotting out positioning and experimenting with poses. In fact, it seems as though he flipped the figure to show the left side as opposed to the right in this study. Later sketches (held at the MFA) shows the figure in its “final” position.

The Joyful Mysteries panel contains scenes of The Annunciation, The Visitation, The Nativity, The Presentation, and The Finding of Our Lord in the Temple. Two sketches for these scenes are more completed; instead of quick, impressionistic mark-making, Sargent shows an assiduous attention to detail, with heavier lines creating more rounded forms. Again, his interest in drapery is apparent in the deep pockets of shadow that contrast with the flatter areas of crosshatching, where Sargent only indicates darkness. The third sketch, more economical, focuses on the hands holding the nails used in the Passion, which were rendered in gold relief in the final panel.

This panel illustrates the fate of the worthy souls approaching the gates of Heaven. The white-robed figures ascend into the sky, holding hands and entwined with others, some playing golden harps. In this sketch, Sargent focuses on the flexed leg of the figure, repeatedly articulating the muscles and tendons of the angel in the final panel. It is notable that in this brief sketch, Sargent still manages to convey a sense of weightless ascension.

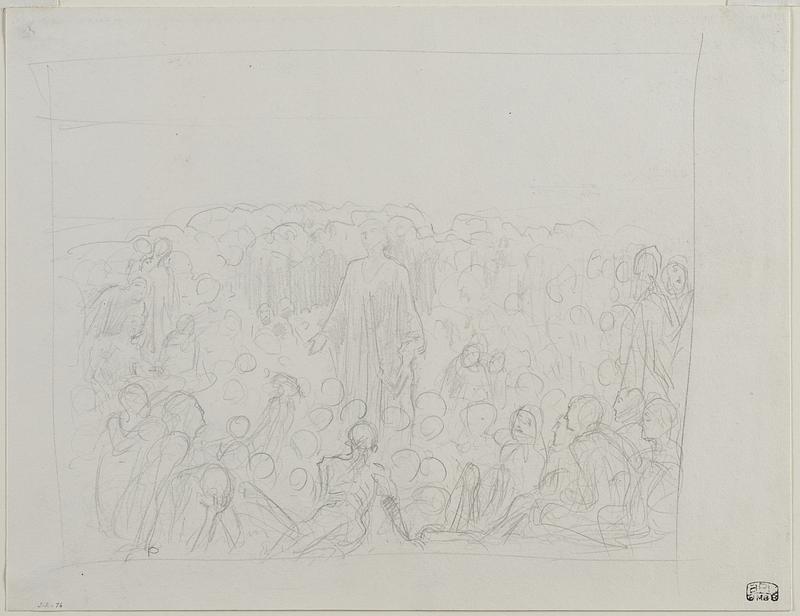

Sargent never finished the Triumph of Religion mural cycle, increasingly preoccupied with his mural commission at the Museum of Fine Arts and dying of a heart attack in 1925. His sketches are all we have to reconstruct his final vision. From sketches like this final one, we can determine that he intended to show an austere Middle Eastern landscape with Christ at the center of a large crowd of figures. This remaining sketch, austere but evocative, serves as a poignant trace of what Sargent left unfinished in practice, but not in spirit.

Add a comment to: John Singer Sargent’s Sketches for His Triumph of Religion Murals