The American woman's rights movement grew out of the 19th-century abolitionist movement and had important roots in Boston. The Boston Public Library holds an extensive collection of abolitionist materials that includes significant correspondence by leading women's rights activists. This blog highlights a few of those "early workers" and their contributions to the ratification of the 19th amendment.

Early Individual Efforts, 1756-1845

October 30, 1756 – Lydia Chapin Taft is the first woman to legally vote in colonial America (Uxbridge, Massachusetts Colony).

March 1776 – Abigail Adams writes to John Adams :“I desire you would remember the ladies. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation."

1790 - Judith Sargent Murray publishes her essay “On the Equality of the Sexes ” in the Massachusetts Magazine two years before Mary Wollstonecraft published Vindication of the Rights of Women.

1833 – Lucretia Mott, Abby Kelley Foster and Lucy Stone are among the early reformers who helped the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison establish the American Anti-slavery Society.

July 29, 1840 - Lucretia Mott writes to Maria Weston Chapman about her experience at the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London where she was denied participation because of her gender. It was there where she met Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The exclusion of women at this meeting was the impetus for the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.

1845 - Margaret Fuller publishes Woman in the Nineteenth Century. This book is widely considered to be the first book on women’s rights in the United States. It inspired a generation of women.

The Women Organize, 1848-1860

Just as the American Revolution was started by a tea party, so to was the long battle for women to win the right to vote. On July 9, 1848, Jane Hunt invited Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary M’Clintock, Lucretia Mott and Martha Coffin Wright to her home for tea. During their visit, they decided to hold a women's rights convention—the Seneca Falls Convention—to discuss the “social, civil, and religious condition and rights of women.” Stanton introduced the Declaration of Sentiments, which included the first formal demand made in the United States for women's right to vote. 300 people attended the first convention, and sixty-eight women and thirty-two men signed the Declaration of Sentiments.

Two years later, on October 23 - 24,1850, delegates from most of the northern states met in Worcester, Massachusetts to discuss woman’s rights. Elizabeth Cady Stanton considered this to be the first national convention on women’s rights because, unlike Seneca Falls, it created a group of standing committees. These committees initiated the first efforts at organizing the woman’s suffrage movement. The convention was organized by Lucy Stone and several other women’s rights activists, including Lucretia Mott.

The second National Women's Rights Convention was again held in Worcester on October 15, 1851. This was just one of the seven conventions that took place throughout the country during the 1850s where the laws of the United States were challenged, resolutions were passed and strategies were implemented.

One of most important conventions was held in Akron, Ohio in 1851, where Sojourner Truth asked "Ain't I a woman?" and decried the inequality experienced by Black women. By the beginning of the Civil War, women were speaking out about gender equality and making strides in social reform.

Activism During the Civil War Years, 1861-1864

During this time women reformers, most of whom were abolitionists, turned their efforts to the war effort. On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation which granted freedom to enslaved Blacks in Confederate states. However, this did not go far enough for Elizabeth Cady Stanton or Susan B. Anthony.

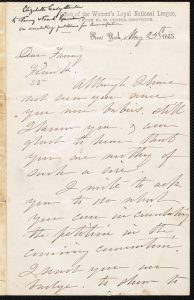

In May 1863, they established the Women’s Loyal National League. Their purpose was to sign and circulate petitions that would call for an end to the Civil War by a constitutional amendment. The League delivered almost 400,000 signatures to Congress and was a major force in the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Through this effort, the Women's Loyal National League became the first national women's political organization in the United States, and it legitimized the women's movement.

The 15th Amendment and the Split, 1866-1869

In 1866, the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention was held in New York City. Led by Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony it was transformed into the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) whose purpose was to campaign for universal suffrage. As the passage of the 15th amendment became more certain, the membership became increasingly more divided. Stone advocated for Black men to be granted the vote before women. She also wanted to maintain ties with the abolitionist movement. Stanton and Anthony, however, were steadfast in their demands that both women and Black men should given the vote at the same time. They immediately severed ties with the abolitionists.

Consequently, in November 1868 Julia Ward Howe and Lucy Stone formed the New England Woman Suffrage Association (NEWSA). NEWSA was the first major political organization dedicated to women’s suffrage. The 15th amendment was passed on February 26,1869.

Two days later, Anthony and Stanton formed the more radical National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). A few months later, Lucy Stone, Julia Ward Howe and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin founded the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

Competing Voices: The Revolution and The Woman’s Journal

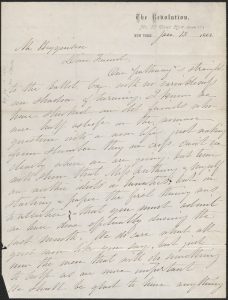

In a letter to Thomas Wentworth Higginson dated January 13, 1868, Elizabeth Cady Stanton laid out the aims and principles of the editors of The Revolution. The Revolution was the official organ of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association; published in New York from 1868-1872.

The paper reanimated the woman’s rights movement after the Civil War. It established a readership among working-class women by reporting on social issues affecting working-class women.

Lucy Stone began editing and publishing the Woman's Journal, which would be "devoted to the interests of Woman, to her educational, industrial, legal and political Equality, and especially to her right of Suffrage. " It was published in Boston from 1870-1931.

Victoria Woodhull, History of Woman Suffrage, and Signs of Reconciliation, 1870s-1880s

At the same time these newspapers were being published, reformer Victoria Woodhull and her sister Tennessee Claflin founded Woodhull and Claflin's Weekly. Like The Revolution, the Weekly promoted such causes as women's suffrage and labor reform. It also advocated for free love. Woodhull’s interest in women’s rights began in 1869 when she attended a woman's suffrage conference. She announced that she was running for president in 1870. In 1871, she became the first woman to deliver speech on women's right to vote before the House Judiciary Committee. There, she argued that the 14th and 15th amendments gave women the right to vote. This put her in a position of prominence with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Woodhull was arrested for mail fraud right before the 1872 presidential election and spent election night in jail. She was not invited to speak at another suffrage convention after her run for president.

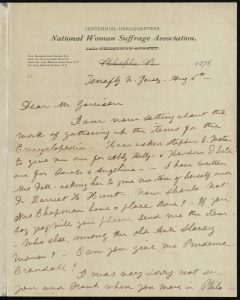

On August 6, 1876, Susan B. Anthony wrote to William Lloyd Garrison telling him that she was staying with Elizabeth Cady Stanton at her home in New Jersey. She was "working for dear life trying to pick up and bring together some of the broken and scattered threads of our woman suffrage work in the past 28 years - and put it on paper too - that the future student of history may have data from the early workers . . ." In 1881, Anthony, together with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage, published the six volume History of Woman Suffrage (1881-1922). The first volume is comprised of the stories of the first activists.

The 1880s was a challenging decade for the two wings of the movement. The leaders were unsuccessful in generating enthusiasm for their positions. Early attempts to unify yielded no results, and the younger women on both sides were becoming impatient with the split.

Thus, in November 1887, the AWSA passed a resolution for Lucy Stone to talk with Susan B. Anthony about the possibility of a merger. Anthony, Stone, Rachel Foster Avery (an officer of the NWSA), and Alice Stone Blackwell (an officer of the AWSA and Lucy Stone's daughter), met in Boston in December 1887 for the first of many discussions.

National American Woman Suffrage Association, the rise of Black Women's Activism and the Legacy of the First Wave Suffragettes, 1890-1920

Brokered in large part by Alice Stone Blackwell, the National American Woman Suffrage Association was formed on February 18, 1890. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was its first president. This was the first single national organization of the suffrage movement. Even with the reconciliation of the two groups, differences still remained. Although Black women were allowed to participate on the national level, they were largely excluded from state and local level organizations.

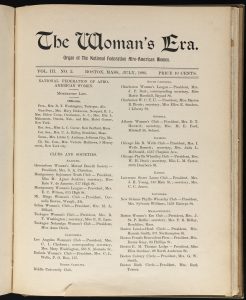

In 1894, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, who helped Lucy Stone form the American Woman Suffrage Association, started The Woman's Era (1894-1897). It was the first newspaper edited and published by a Black woman in the United States.

The paper, whose Boston office was very near The Woman's Journal, advocated for women's suffrage and Black female activism. It also featured interviews with prominent Black female activists such as Ida B. Wells. Between 1892 and 1894, Ruffin founded the Woman's Era Club, the first Black women's club in Boston and one of the largest in the country. In 1895, the club proposed to hold a national conference for Black women. On July 29, 1895, representatives from 42 Black women’s clubs from 14 different states met at Berkeley Hall in Boston for the first National Conference of Colored Women of America. Josephine Ruffin presided.

Not all women wanted to vote; some felt that the women’s rights movement had passed reforms and resolutions that made voting unnecessary. In response to this, women in Boston founded the Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women in May 1895. Massachusetts was the first state to have an anti-suffrage organization. However, by this time, women from all backgrounds were becoming an important part of public life. Recognizing the progress women had made, Susan B. Anthony stepped down as the president of the NAWSA in 1900 and named Carrie Chapman Catt president. Catt would ultimately lead the second wave suffragettes in the successful passage of the 19th amendment in 1920.

Additional Resources: The BPL's Anti-Slavery Collection and Related Women's Rights Activists Correspondence

The Anti-Slavery Collection

In the late 1890s, the family of William Lloyd Garrison, along with others involved in the anti-slavery movement, presented the Boston Public Library with a major gathering of correspondence, documents, and other original material relating to the abolitionist cause from 1832 until after the American Civil War. Included in this extraordinary collection is a substantial amount of letters from the leading early women's rights activists who were also committed abolitionists. These women worked tirelessly with William Lloyd Garrison as well as Samuel May, Jr., and Wendell Phillips both in the abolitionist movement and advocating for equal rights. Along with correspondence by Lucretta Mott, Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the collection contains letters from such activists as Mary Rice Livermore, Anna Dickinson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Lydia Maria Child, Abby Foster Kelley and Angelina and Sarah Grimké.

The letter that started the movement . . .

Related Manuscript Collections

Thomas Wentworth Higginson Correspondence, 1848-1908

Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1823-1911, was an abolitionist, author, Civil War colonel of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, and Unitarian minister from Cambridge, Massachusetts. Higginson was a supporter of the women’s suffrage movement and helped organize the American Women Suffrage Association in 1869. He also served as editor and contributor for The Woman’s Journal. Of the letters in this collection, many deal with abolition, women’s suffrage, and literature. Correspondents include abolitionists, writers, and suffragettes such as Lydia Maria Child and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Also included is correspondence from Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, and Abby Kelley Foster. Collection finding aid

Margaret Fuller Papers, 1837-1884

This collection contains approximately 154 letters, poems, fragments, and journal extracts written by Margaret Fuller (1810-1850) from 1837 to 1850. It includes letters to William Henry Channing, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Lewis Cass. This material provides insights into Fuller's thoughts about religion and nature, her writing, the Dial, her dissatisfaction with life, her relationships with Emerson and Ossoli, and her experiences in Italy. Also included are 109 letters written between Thomas Wentworth Higginson and such people as William Henry Channing and James Freeman Clark. There is also correspondence with George Willis Cooke regarding his biography about Fuller. Collection finding aid

Victoria Woodhull Papers, 1883-1927

The letters in this collection document the relationship between Victoria Woodhull Martin and her husband, John Biddulph Martin, and date from 1883-1927. Through newspaper clippings, manuscript fragments, and Zula Martin’s notes of her attempted biography of her mother, the collection documents Woodhull’s life long interests in equal rights, women’s issues, and marriage and divorce. It also provides glimpses into Woodhull’s character. Collection finding aid

Related Manuscript Material

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. Autograph and Commonplace Book, 1831-1841.

Selected readings

Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement

African African American Women and Social Action

African American Women and the Vote, 1837-1965

Add a comment to: “Help to make the world better”: Lucy Stone and the First Wave Suffragettes