When transcribing letters from the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts project, you may come across letters in which important figures, such as Lydia Maria Child, discuss the American Anti-Slavery Almanac. On June 20, 1860, Child wrote to William Lloyd Garrison about an almanac they planned to publish, asking Garrison, “How many pages do you propose to have?...If you have illustrations, they ought to be much handsomer, than those in the old almanacs. The taste of the times requires it.” From text to illustrations, Child and Garrison made sure to present a unified message in the almanacs printed for the American Anti-Slavery Society.

From the 17th century to the 19th century, Americans bought and often checked almanacs. They did this to predict the weather, mark low and high tide, or record daily thoughts, like the way we use diaries today. The Boston Public Library has digitized much of the Anti-Slavery Collection, now available at Digital Commonwealth and the Internet Archive. There, you can browse the almanac of William Lloyd Garrison and a collection of American Anti-Slavery Almanacs from 1836 to 1847. The opening pages of the American Anti-Slavery Almanac typically included fiery criticisms of slavery by abolitionists. In addition, when words failed, they used illustrations to show the evils of slavery to a Northern audience.

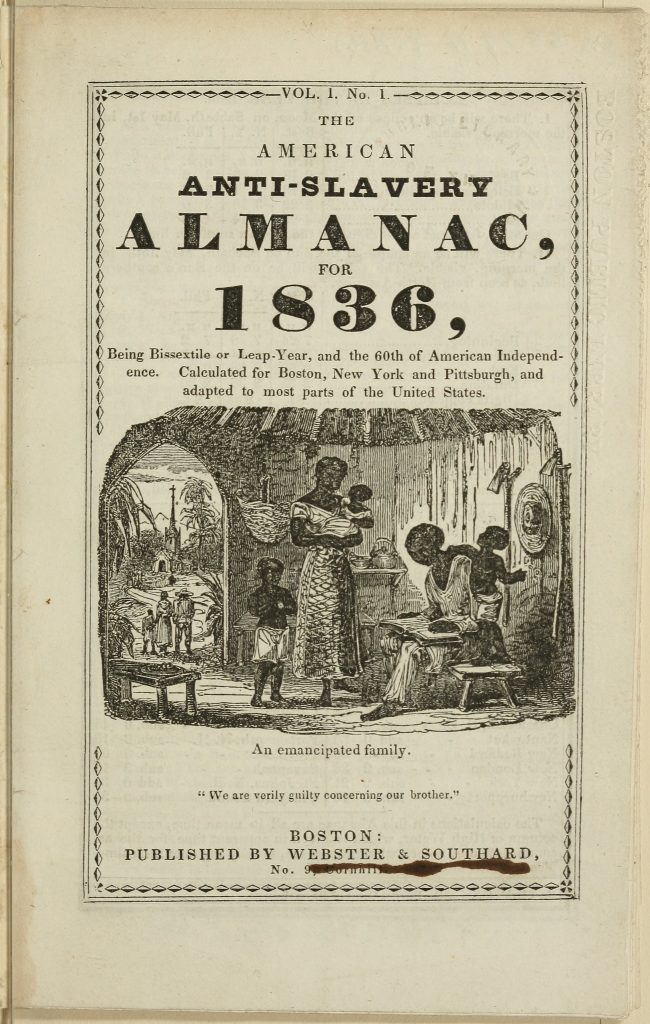

On the cover of the first American Anti-Slavery Almanac from the year 1836, an illustration (above) presents a pleasant image of an African family freed from slavery. It is unclear if this is a free black family now back in Africa, or if this is an African family who never faced slavery. Founded in 1817, the American Colonization Society helped transport free blacks to Liberia, a controversial program backed by both anti-slavery and pro-slavery supporters.

Within the American Anti-Slavery Society, members held a range of opinions on African resettlement. In an 1832 essay titled Thoughts on African Colonization, Garrison critiqued the American Colonization Society's goals as helpful to slaveholders who feared that free blacks would cause slaves to revolt. It is therefore unlikely that Garrison was involved in the selection of the drawing above.

In the background of the image, palm trees place the family in an imagined idea of Africa as a tropical paradise. A church seen through the doorway would have reassured Christian readers that the family would continue their faith in Africa. The seated father reads aloud from a book, possibly the Bible, reminding readers that the South outlawed the education of slaves because Southern whites believed that literacy could lead to the overthrow of slavery.

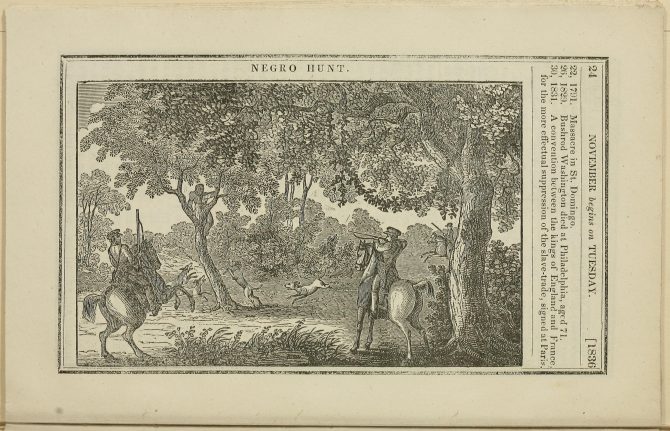

While the cover illustration presents an idealized alternative to slavery, a print inside the almanac shows a dreadful scene of a “Negro Hunt,” in which three armed white men on horseback chase down a black man, who scrambles up a tree to avoid the jaws of hunting dogs. Abolitionists often argued for the humanity of African Americans, and the illustration shows to what level Southern masters treated slaves as animals, who could be hunted down if they escaped. Each day, Northerners would find such emotional images in their personal Anti-Slavery Almanacs, which could convince them to join the abolitionist cause. For the American Anti-Slavery Society, the almanac therefore served as an important tool for spreading its arguments against slavery and for getting new supporters.

Kelsey Gustin, the author of this post, is a Humanities PhD intern at the Boston Public Library and a doctoral student at Boston University in the History of Art and Architecture. She specializes in nineteenth and twentieth-century American art and is presently writing her dissertation on representations of working-class immigrants in New York City from 1890 to 1920.

Kelsey Gustin, the author of this post, is a Humanities PhD intern at the Boston Public Library and a doctoral student at Boston University in the History of Art and Architecture. She specializes in nineteenth and twentieth-century American art and is presently writing her dissertation on representations of working-class immigrants in New York City from 1890 to 1920.

Add a comment to: The American Anti-Slavery Almanac