This post is Part II of a series. Read Part I.

1868-1869: The Coming of the House Sparrow

I have yet to find any official discussion of the house sparrows’ introduction to Boston in the City Council Proceedings or other city documents.

There is, however, a record of acquisition in the Auditor of Accounts’ Fifty-Seventh Annual Report of the Receipts and Expenditures of the City of Boston and the County of Suffolk, State of Massachusetts, for the Financial Year 1868-69 (May 1, 1868 to April 30, 1869, inclusive), published as City Document no. 61 for that year.

In that august publication we learn that $57.50 was paid for “Twenty-Three English Sparrows,” so these must be at least some of the birds introduced in those years.

Some additional details of the introduction are available from a November 9, 1871 article by George Punchard in the Congregationalist newspaper. (The Congregationalist can be read through the BPL online resource 19th Century U.S. Newspapers, accessible with your BPL card or eCard and PIN).

According to Punchard, of 150 birds ordered by the City “only about twenty reached Boston; and these, even, in a sorry condition; tailless, and nearly featherless. They arrived in the autumn, 1868, and were soon after let loose in the Boylston Street Cemetery.”

This is surely a reference to the Central Burying Ground on the Common near the corner of Boylston and Tremont.

Despite their sad state, it seems these birds somehow survived their first winter and beyond.

1870-1871: Rare Birds Faring Well

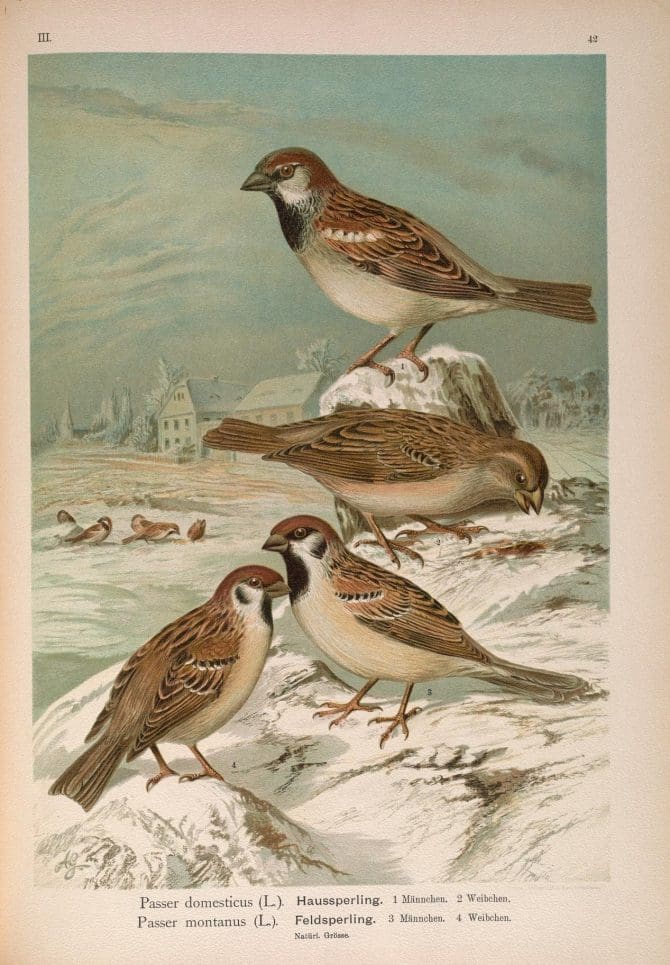

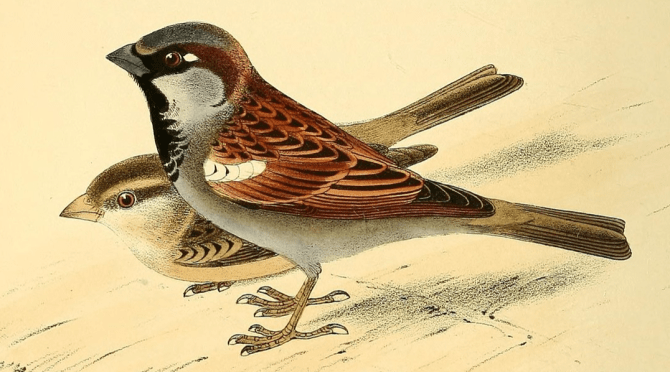

It is amusing today to see house sparrows included in J.A. Allen’s February 1870 American Naturalist article “Notes on Some of the Rarer Birds of Massachusetts,” but in 1870 they no doubt belonged, limited as they were in number and range. In Allen’s article we find what is perhaps the earliest account of how the house sparrows of Boston were faring in their new home:

EUROPEAN HOUSE SPARROW. Passer domestica Leach. The few pairs turned loose in the Boston Common a few years since seem to be slowly increasing in numbers, and bid fair to be of great service in checking the ravages of several species of caterpillars that now greatly injure the foliage of the shade trees. These interesting birds are now frequently observable both on the Common and in the Public Garden.

The full article is available through JSTOR.

Punchard’s 1871 Congregationalist article offered more detail about how the birds were faring, noting that from their “unpromising beginning, these prolific little birds have increased, until it is now estimated, that there may be one hundred birds, on and around the Common and Public Garden, for every bird which was let loose there three years ago.”

Both Allen and Punchard were decisively pro-sparrow and convinced of their value as insect predators, with Punchard noting that “Not for years has the foliage of the Common been so free from insects…thanks to these little wood rangers.”

Not everyone was convinced of their value, however.

1870s: The War in Print

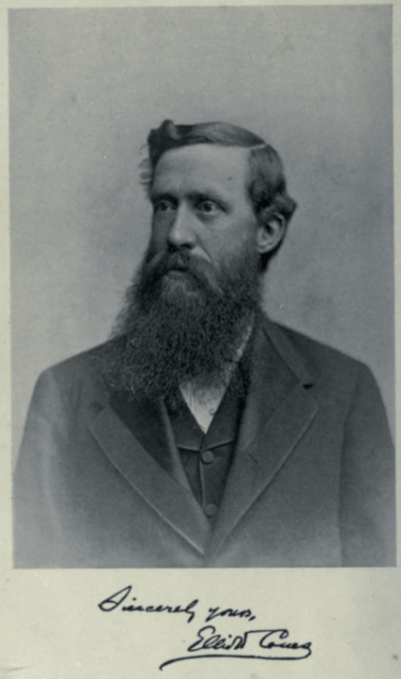

Over the next decade a running conflict over the house sparrow emerged in the newspaper and periodical literature of the country, as evidenced by an extraordinary 1879 bibliography published by anti-sparrow doctor and ornithologist Elliott Coues (pictured at right) in the Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories.

In his introductory remarks Coues is clear about his attitude toward the sparrows, calling them “objectionable,” “noxious,” and a “plague.” In fact, so convinced is he of the general opposition to the sparrows that their only remaining major defender, he claims, is Thomas Mayo Brewer, whom we saw previously coming to the sparrows’ defense before their introduction to Boston.

A sizable portion of this print debate played out in Boston newspapers (thanks no doubt to Brewer’s involvement), including the Boston Daily Advertiser, the Boston Journal, and the Boston Evening Transcript.

For more on Coues and the written debate over the house sparrow in the US, see Michael J. Brodhead’s 1971 “Elliott Coues and the Sparrow War” in The New England Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 3, , 1971, pp. 420–32, accessible through JSTOR using your BPL card or eCard and PIN.

Join us next time to learn how the sparrow war became a reality in Boston.

Add a comment to: The House Sparrow in Boston, Part II