From 1831 to 1865, William Lloyd Garrison, a vocal white abolitionist, edited a weekly newspaper, titled The Liberator, in Boston, Massachusetts. When other abolitionists supported a slow end to slavery, Garrison vowed from the very first issue of The Liberator to “strenuously contend for the immediate enfranchisement of our slave populations,” which was a radical position at the time. When transcribing letters for the Anti-Slavery Manuscripts Project, you will come across many letters between Garrison and other abolitionists about The Liberator. The Boston Public Library has digitized many issues of The Liberator, which are now available online at Digital Commonwealth.

In the pages of The Liberator, Garrison printed articles by both white and black abolitionists. These included female writers, at a time when women were discouraged from entering the political arena. As a supporter of women’s rights, Garrison faced repeated criticisms for his eager involvement of women in the abolitionist movement. Some of the most influential abolitionists in Boston were women, including Lydia Maria Child and the Weston sisters, whose letters form a large portion of the Anti-Slavery Collection.

From the start, the newspaper was not popular among whites. If it wasn’t for the support of free blacks, who made up three quarters of its subscribers, The Liberator would not have survived. In an 1865 letter, the black abolitionist William Cooper Nell wrote that during its “first year, the Liberator, was supported by the colored people, and had not fifty white subscribers.” James Forten was a wealthy businessman from Philadelphia, who wrote to Garrison. His letters reveal how black abolitionists eagerly gathered subscribers and support for the periodical. On February 2nd, 1831, Forten wrote in a letter to Garrison, “I am sure it will grafity you to learn that the Liberator is highly valued here by all who have had opportunity to judge of it and others who have already heard of it are very anxious to peruse it.” Garrison noted the popularity of The Liberator particularly among African Americans, in a February 14, 1831, letter, writing,

“Upon the colored population, in the free states, [The Liberator] has operated like a trumpet-call. They have risen in their hopes and feelings to the perfect stature of men: in this city, every one of them is as tall as a giant. About ninety have subscribed for the paper in Philadelphia, and upwards of thirty in New-York, which number, I am assured, will swell to at least one hundred in a few weeks.”

Without the support of black abolitionists, The Liberator would not have spread its influence and message as far as it did over its thirty-year life.

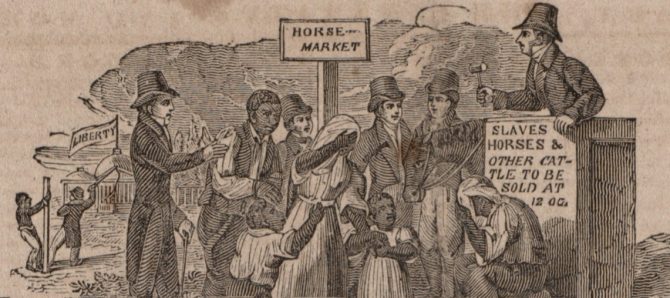

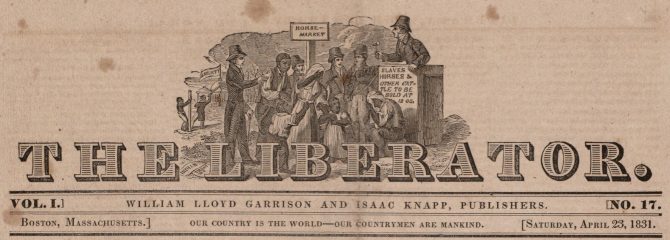

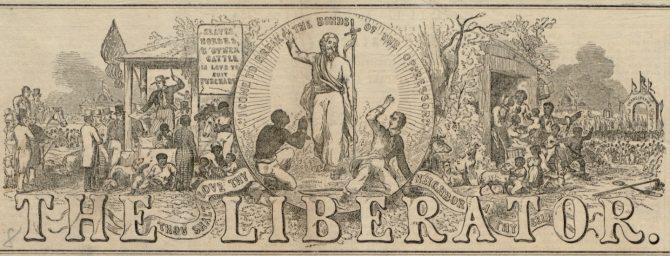

At the top of most issues, the masthead included an illustration that showed the evils of slavery or a vision of an emancipated future. In April of 1831, The Liberator first adopted an illustrated masthead showing a slave auction, in which a family is torn apart on the auction block. At the far left, a black man is whipped by a slave owner within sight of the Capitol Building. The Capitol ironically flies a flag that reads “Liberty”. Abolitionists over and over drew attention to the hypocrisy of slavery in a nation that upheld that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

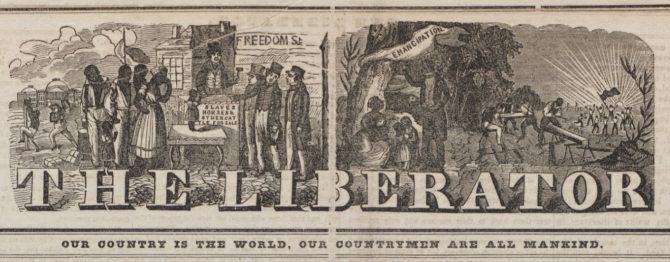

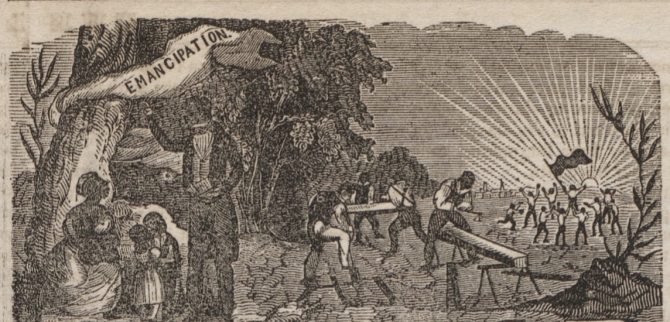

On March 2nd, 1838, Garrison changed the illustrated masthead to include a hopeful scene on the right, of an emancipated family. The scene on the left is of a slave auction, contrasting with the scene on the right. The drawing on the right shows a black middle-class family in a peaceful rural setting, who represent a hopeful future. In the distance, men carve timber logs to build a new America, which is graced by the dawning light of a rising sun.

The masthead did not change again until January 3, 1851, at which point a more detailed scene made up of three episodes showed the same contrasting vision of an enslaved America versus a free America. It was drawn by the white artist Hammatt Billings and engraved by the white engraver Alonzo Hartwell. The illustration depicts a slave auction on the left and an emancipated family on the right. At the center, there is an image of Jesus Christ. He listens to the pleas of a kneeling slave and casts aside a white slave owner, declaring, “I come to break the bonds of the oppressor.” The religious message of the drawing is similar to the spiritual language of the Liberator and reflected Garrison’s own religious views toward slavery.

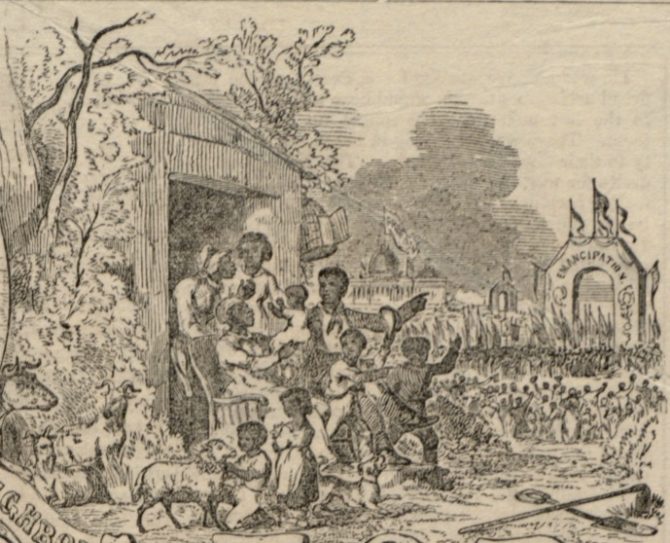

On the right, a black family gestures toward a large parade of marchers who pass through the gates of emancipation. The family lives in a manger-like setting surrounded by animals in a subtle reference to the nativity scene from the Bible. Nearby, there is a plow and a shovel, which are the tools of labor. These are symbolically cast aside, and an open bird cage hangs off the end of the house. This other detail further reinforces the symbolism of a new emancipated age.

Each of the three mastheads of The Liberator mostly focus on the suffering of enslaved blacks and the future promise of emancipated African Americans in America. Garrison did not include any images of white abolitionists (with the exception of an anglicized depiction of Jesus Christ). The images, instead, focus on the struggles, the achievements, and the agency of African Americans, who formed the majority of The Liberator’s readership. To varying degrees, the masthead drawings reflected the activism of black abolitionists. They not only pushed for emancipation, but also equality in the United States, both before the Civil War and afterwards.

Kelsey Gustin, the author of this post, is a Humanities PhD intern at the Boston Public Library and a doctoral student at Boston University in the History of Art and Architecture. She specializes in nineteenth and twentieth-century American art and is presently writing her dissertation on representations of working-class immigrants in New York City from 1890 to 1920.

Add a comment to: The Liberator