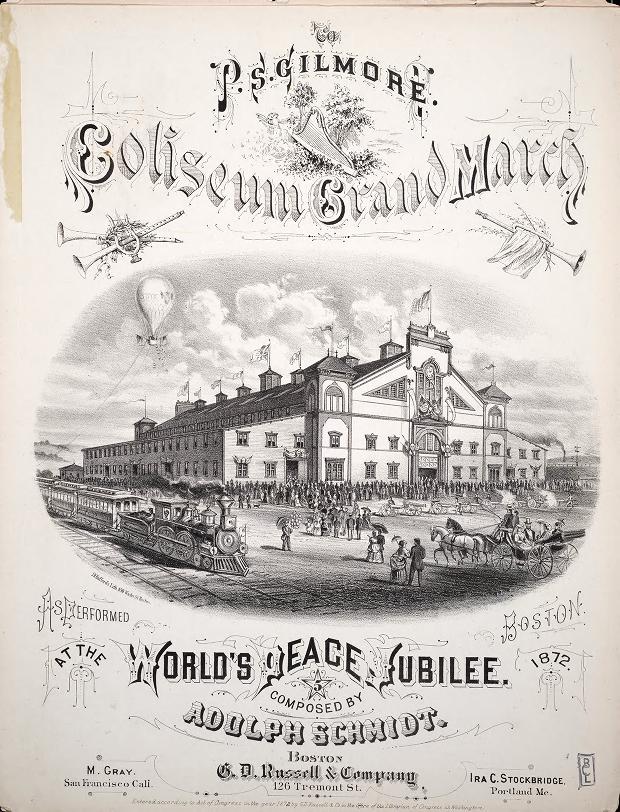

When you think of a multi-day music festival, what comes to mind? Woodstock? Coachella? Newport Folk Festival? One hundred and fifty years ago, Boston hosted a music festival that lasted for 18 days! The World's Peace Jubilee and International Musical Festival took place from June 17 through July 4, 1872, and was held in the Back Bay neighborhood in a Coliseum also known as the Peace Temple. It was created to honor the ending of the Franco-Prussian War. Tickets for the full 18 days were $50 each (over $1,200.00 today!) , and a single concert ticket cost $5.

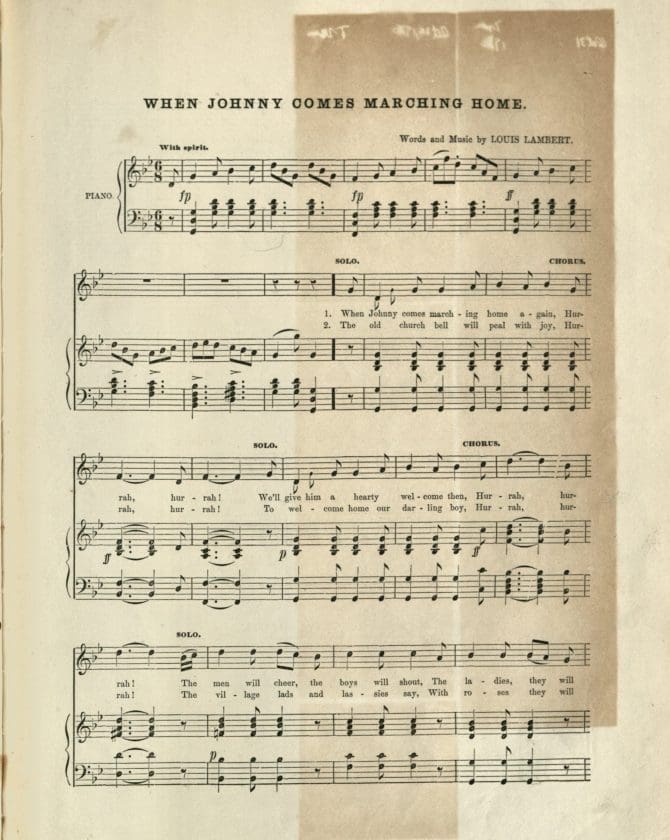

The Jubilee was the brainchild of Patrick S. Gilmore, who had just three years earlier held the National Peace Jubilee and Musical Festival in Boston. That festival was just five days long, and nearly 50,000 people attended it. There were 1,000 orchestra members and 10,000 people in the chorus. Gilmore was an Irish immigrant and one of the leading band leaders in the U.S.A. in the 1860s through 1880s. His other claim to fame was as the writer of the song, "When Johnny Comes Marching Home" under the pseudonym "Louis Lambert" in 1863.

The Coliseum

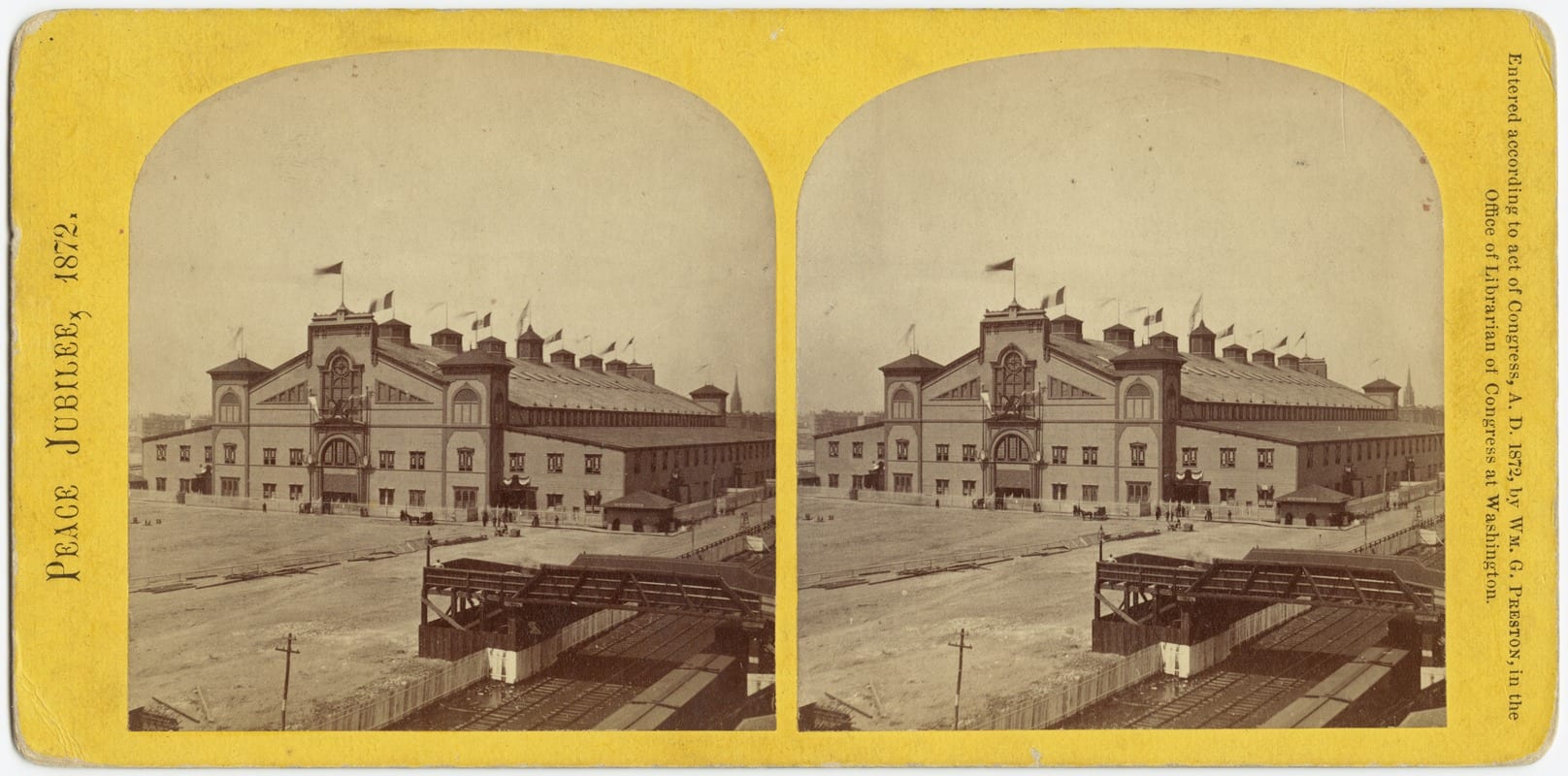

Plans to build the Coliseum started at a meeting held on February 12, 1872. The Coliseum occupied the space that is now filled by the Marriott Hotel and the Copley Place Mall. To build it, the City of Boston first supplied tons of gravel as landfill, with ten trains of gravel arriving every day and 55 men working in around-the-clock shifts to unload and level it out to a depth of two and half feet. The gravel that was used for landfill in this project was later removed and used as street foundations for other parts of Back Bay that were being developed. The building was designed to hold 100,000 people, but a huge storm on April 26 flattened the building as it was under construction only six weeks before the festival was due to begin. Plans were made to continue the festival though with a building at a slightly smaller scale. It ended up being 350' wide and 600' long, with an area of 201,000 square feet and held 60,000 people.

The Jubilee wasn't the only attraction at the Coliseum. Plenty of food vendors set up stalls, and some enterprising individual brought in a captive hot air balloon and situated it near the Coliseum. While the balloon wasn't officially part of the Jubilee, it quickly became associated with it and would show up in advertising and illustrations about the festival.

Besides the music festival itself, two balls were held. One, the "Great Ball," was meant for the public and to honor President Grant and the First Lady and was held on the evening of Wednesday, June 26. 40,000 people were anticipated to attend the event, and the music was supplied by an orchestra of 379 players. The second ball, known as the "Chorus Ball," was less glamorous. The attendees weren't as well-dressed as those at the "Great Ball," and the orchestra was smaller, too, with only 253 players.

Ticket sales for the Jubilee weren't as high as predicted because of a few different factors. All the chorus members had free passes provided to them, which they would pass along to friends and family when they themselves weren't using them. Members of the press and official guests of the City of Boston were also given free passes in the thousands. The largest entrances to the Coliseum were so wide open that ushers were unable to keep people from just walking in without tickets. Plenty of people found that as long as they were content to just hear the music and not see the performances, the thin wooden construction of the Coliseum allowed much of the sound to easily pass to the outside of the building. Finally there was a major heat wave during the Jubilee with outside temperatures in the upper 90s. The temperatures was said to have gotten up to 108 degrees inside the Coliseum, and this led to many people in both the audience and chorus members to faint. The bad weather culminated in a big storm on the final day, which managed to destroy the hot air balloon that was tethered outside of the Coliseum.

No official attendance figures were taken, only estimates. The largest reported attendance took place on July 1 with 70,000 people, which meant that people were standing in the aisles since the Coliseum was only supposed to hold 60,000 people. For the concerts held on the two holidays, Bunker Hill Day (June 17) and the Fourth of July, crowds were considerably lower and only brought in the low thousands.

The Coliseum stood for several mores years, basically unused, until it was bought by a family from Castle Island. They planned to take it apart and use it for its lumber. Some of that lumber went into the construction of triple deckers in Dorchester and East Boston.

The Music and Performers

Not only was the Coliseum slightly smaller than originally intended, so was the size of the instrumental ensemble. Gilmore intended there to be 1,000 musicians making up the orchestra, but there ended up being only 848 because of the difficulty in attracting enough qualified string players. There were also 26 bands that participated in the Jubilee, adding another 529 players. While the mass of band members didn't play as one ensemble by themselves, they did join with the orchestra on some of the pieces. Instrumentalists from out of town were given free round trip rail passage. It has been decided by May to limit the number of chorus members participating to 20,000 singers. In the end, there were 17,282 singers from 165 choral societies (mostly from Massachusetts). While the instrumentalists and soloists were all paid to perform, the chorus members were all volunteers (though they did get free passes to attend the Jubilee).

Dress rehearsals were held in the mornings at 9 am, with the main performances happening in the afternoons. Over the months preceding the Jubilee, the various choral societies had their own rehearsals, but they didn't rehearse as one ensemble until the morning of the first performance. Some evenings there would be a secondary concert, usually either by one of the bands or by the organ. The more challenging works on the programs were performed by a select orchestra and a vocal "Bouquet of Artists" that had the most experienced musicians in their ranks. Some evenings there would be a secondary concert, usually either by one of the bands or by the organ.

One notable group that performed at the 1872 Jubilee was the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who appeared in an augmented group of 150 singers. The original nine singers later performed a second concert during the Jubilee. Their appearance was well-regarded, and led to an invitation to appear before President Grant at the White House. The biggest star on hand was Johann Strauss, Jr. He was there to conduct several of his own works, including the Jubilee Waltz that he wrote especially for the occasion. Strauss made quite an impression as this small man who conducted with his violin on top of a tall podium, making it worth the $100,000 that Gilmore paid him.

Besides the orchestra and bands, there were some other special instruments included in the Jubilee. A "Great Organ" was specially built for the Jubilee by J. H. Wilcox & Co. of Boston. The tallest pipe was 43' from the gallery base. A "Great Drum" was also specially constructed for the event. It was 12' in diameter and 36' in circumference and weighed nearly six hundred pounds. The drum head was so large that when beaten it wouldn't vibrate properly, though, so was used as decoration. 100 anvils varying in weight from 100 to 300 pounds were imported from Birmingham, England. They were played by 100 men from the Boston Fire Department and caused quite a stir. Outside of the Coliseum were cannons and church bells. These were signaled using telegraph to let the operators know when to "play" these items.

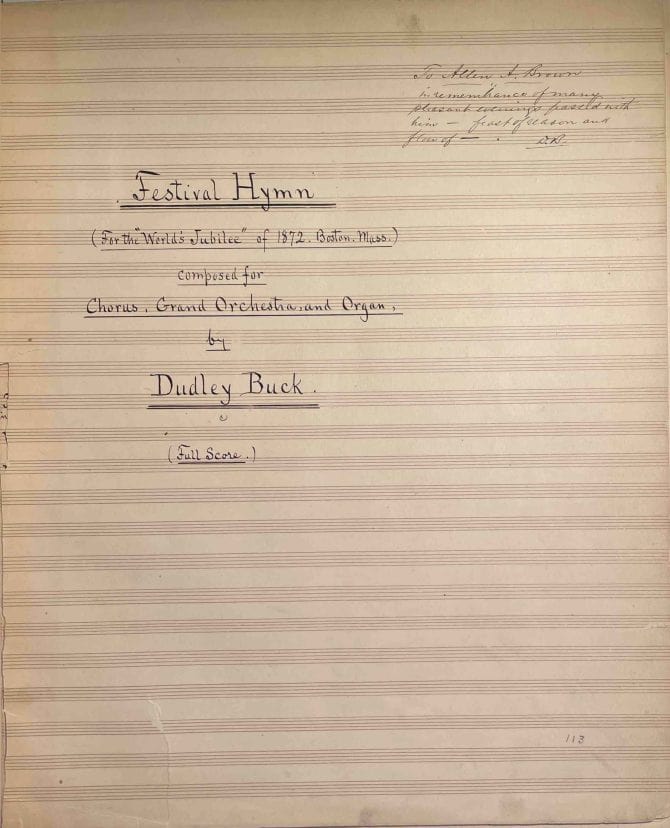

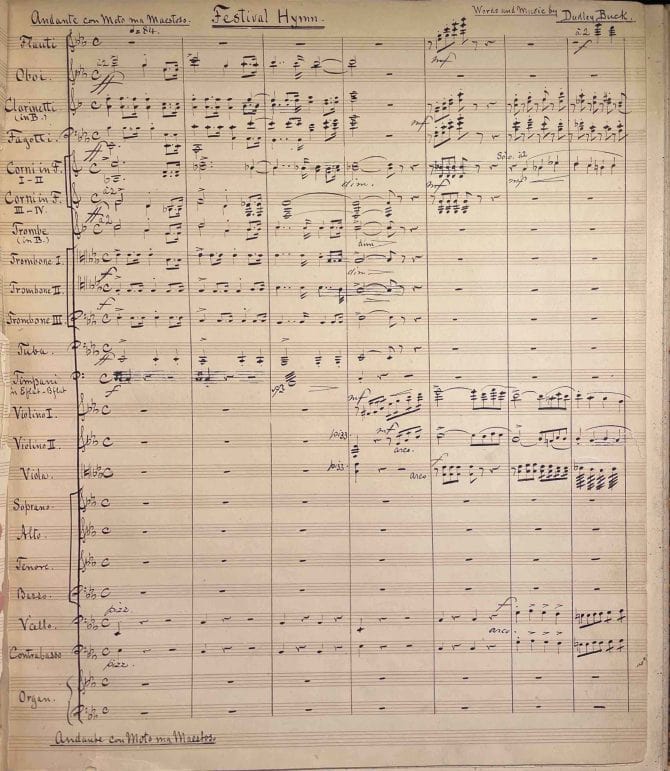

Several works were composed especially for the Jubilee, including the aforementioned Jubilee Waltz, by Johann Strauss Jr., Festival Hymn by Dudley Buck, and Our Nation's Song by H. Millard. The Special Collections department of the Boston Public Library owns a manuscript copy of Buck's work (the title and first pages of which are shown here) that is inscribed to Allen A. Brown, a local amateur musician and collector of music who donated his collection to the library, forming the beginning of a research collection in music at the library.

The Jubilee was well received by the local press, with one exception. Sullivan Dwight, who was the editor of the Journal of Music, especially hated the festival. While Gilmore wanted the event to appeal to the widest number of people and so programmed music that included classical works, patriotic tunes, popular songs, and hymns, Dwight thought that it should have been purely a classical music festival. He was a musical snob, however, and wasn't the populist that Gilmore was.

Library Resources for More Information

Printed Music

Jubilee Waltz [Brown Collection]

Our Nation's Song [Music Research Collection]

Our Victorious Banner [Brown Collection]

Selections for World's Peace Jubilee of 1872 [Music Research Collection]

Books

Hand-book, With Illus. and Diagram of the Coliseum [Music Research Collection]

Jubilee Days [Music Research Collection]

Grand Jubilees [Music Research Collection]

Johann Strauss in Boston [Music Research Collection]

Patrick Gilmore's Boston Peace Jubilees [Music Research Collection]

Add a comment to: World’s Peace Jubilee and International Music Festival