Explore the built heritage of the Central Library in Copley Square with our virtual Art & Architecture booklet, funded by Bank of America.

Art & Architecture Booklet

Virtual Tour of the BPL

Central Library Points of Interest

Central Library Background

McKim Building Exterior

The proportions of the building, which is wider than it is tall, and its large, arched windows on the second story are modeled after the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris. The exterior decorations reference the history of both Boston and the library: the green cornice along the roofline is made up of dolphins and seashells, intended to represent Boston’s maritime ties; while 537 names of writers and thinkers are carved into the outside of the building, giving visitors a hint of the books they might find inside. If you don’t recognize many of these names, you’re not alone. A 1979 article in the Boston Globe referred to the building’s architect, Charles Follen McKim, as a “drearisome name-dropper" for including so many names that are unfamiliar to most people.

The central entrance on Dartmouth Street is made up of three arched doors. Above the center doorway is the head of Minerva, Goddess of Wisdom, and the library’s motto and guiding principle: Free to All. The carvings above each of the three doors, just below the windows, are the seals of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the Boston Public Library, and the City of Boston.

The seals were carved by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, a friend of McKim’s. He had also planned to sculpt two groups of figures to be placed on either side of the entrance. Saint-Gaudens died before he could complete the sculptures, and the empty spots were eventually filled by one of his students, Bela Pratt. Pratt’s two bronze sculptures remain on the front steps of the library today. The figure holding a globe represents Science, and the figure holding a paintbrush and artist’s palette represents Art.

McKim Building Lobby

Just inside the McKim building entrance on Dartmouth Street are three interior doorways leading from the vestibule to the lobby. Within these doorways are pairs of bronze doors cast by Daniel Chester French. Each door weighs 1,500 pounds and features an allegorical figure. Each figure represents a genre of literature, named at the top of each door.

The arched ceilings inside the lobby are the work of Rafael Guastavino, a Spanish architect who specialized in vaulted ceilings constructed of interlocking ceramic tiles. Guastavino was awarded the project because he assured building architect Charles Follen McKim that his ceilings would be lightweight, strong, and fireproof — all important qualities in a library building. This is the first construction project that Guastavino worked on in the United States, and his ceilings are now in many public and private buildings, including Grand Central Terminal in New York City. His exposed tile patterns, which became his trademark, are visible in the ceiling of the Washington Room, among other spaces in the library. In this space, Guastavino’s ceilings are decorated by tiled mosaics installed by Italian craftsmen who had immigrated to Boston’s North End. They include the names of famous citizens of Massachusetts, grouped by profession.

The brass zodiac signs in the lobby floor were transferred to the BPL from a building at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. They were placed alongside the library’s seal and a list of early benefactors, located at the bottom of the stairs.

Grand Staircase & Puvis de Chavannes Gallery

The McKim building’s main staircase, often referred to as the Grand Staircase, was architect Charles Follen McKim’s centerpiece. He hand-picked each piece of yellow Siena marble for the walls and installed them in a carefully designed pattern so that the colors of each block complement each other. The two lion sculptures are carved from the same yellow marble and were unpolished when they arrived at the library. Veterans from two Massachusetts regiments that fought in the US Civil War commissioned the lions in memory of their fallen comrades. When the veterans saw the statues, they decided that the unpolished stone was a fitting tribute and asked that they remain that way, which is how you see them today. Library lore says that rubbing the lions’ tails will bring good luck.

The murals surrounding the staircase were painted by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. They are his only work outside of France, and he took the commission on the condition that he would not travel to Boston. He painted the murals on canvas in his studio in Paris and then shipped them to Boston, where they were attached to the wall using a special paste. The large panel that spans the wall across from the top of the staircase depicts the Spirit of Enlightenment, seen above the doorway to Bates Hall, greeting the Muses of Inspiration. The eight panels surrounding the stairs each represent a discipline of human knowledge: philosophy, astronomy, history, chemistry, physics, pastoral poetry, dramatic poetry, and epic poetry. You can refer to the mural guide in this space to learn more.

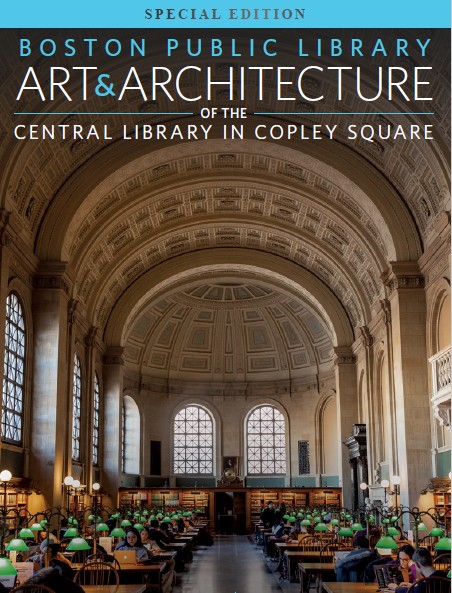

Bates Hall

Bates Hall is the original reading room at the Central Library and remains a favorite spot for reading and quiet study. The space spans the entire length of the McKim building and boasts a towering 50-foot barrel vault ceiling. While there were several mural paintings proposed for this space during the building’s construction, none were completed. Much of the room is original, including the tables and bookcases, and other features have been restored to match its 1895 appearance, such as the signature green lamps. Busts of authors and other historical figures line the walls.

The space is named for Joshua Bates, the BPL’s first major benefactor. Bates grew up in nearby Weymouth, Massachusetts, without a public library. He was self-educated and recognized the importance of the library’s mission, so he offered a generous donation when the library was founded. As conditions of his gift, he requested that the library be warm and well lit, provide space for at least 150 patrons to read, and remain free to all. Bates’s words “free to all” remain the library’s motto and guiding principle.

Abbey Room

The Abbey Room first served as the book delivery room. When the library opened, most of the books were stored on bookshelves that were closed to the public, or “closed stacks,” and patrons had to request their materials to be retrieved by library staff. To facilitate these requests across such a large building, patron requests would be sent through a pneumatic tube system, and the books would then be sent back along a book railway. Because patrons had to wait for these requests to be fulfilled, architect Charles Follen McKim hoped to provide something for them to look at in the space. He asked his friend, the illustrator Edwin Austin Abbey, to create a series of paintings for this room. Abbey eventually settled on a retelling of Sir Galahad’s Quest for the Holy Grail, depicted through 15 panels. Sir Galahad’s red cloak makes him recognizable in each panel as he moves through his story. You can refer to the mural guide in this space to learn more.

The book delivery desk was relocated to the opposite side of the building during a renovation in the early 2000s, leaving this space open for special events and for patrons to enjoy the paintings. Though the pneumatic tube system and book railway are no longer in operation, the library continues to store thousands of items in the closed stacks, and library staff are on hand to retrieve them.

Sargent Gallery

This skylit hall on the McKim building’s third floor, containing a mural cycle by John Singer Sargent, originally served as the lobby for the adjacent special libraries, which we refer to today as Special Collections. Sargent was known primarily for painting portraits when he took on this project, and he saw this as an opportunity to create something that might elevate his artistic reputation. Sargent spent more than 30 years working on these murals. He first discussed the idea with architect Charles Follen McKim in 1890, and the planned final installation remained unfinished when he died in 1925. Sargent painted the existing mural panels in England and traveled with them to Boston for four separate installations between 1895 and 1919.

Sargent saw this as an immersive project and thought carefully about how patrons would experience the space, at one point going as far as to build a scale model of the gallery in his studio. His work on the project extended beyond the paintings themselves to features such as the gold molding on the ceiling, light fixtures, and the bookcases, each of which Sargent chose or designed. Sargent titled the entire work Triumph of Religion and depicts a broad range of moments and iconography from early Egyptian and Assyrian belief systems, Judaism, and Christianity. The paintings are shaped by Sargent’s own views of these various religious traditions and have been the subject of criticism and controversy. You can refer to the mural guide in this space to learn more.

Courtyard

The library’s courtyard was designed to be an oasis in the city, providing a peaceful spot for patrons to enjoy the outdoors. The design, with a covered walkway, called an arcade, surrounding an open plaza, is based on the courtyard of the Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome. Atop the central fountain stands the bronze sculpture Bacchante and Infant Faun, which architect Charles Follen McKim gave to the library in memory of his late wife. The sculpture is of a nude female figure balanced on one leg, holding a baby in her left arm and dangling a bunch of grapes from her right hand.

Bostonians were outraged by the sculpture when it first arrived at the library in the 1890s because of her perceived drunkenness, her nudity, and the fact that she was exposing a baby to this behavior. McKim withdrew the gift because of the controversy and gave it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, purchased a copy so that Bostonians could continue to see it. During a courtyard renovation in the 1990s, the BPL had a copy made of the Museum of Fine Arts’ copy so she could finally make her way back to her original location.

Boylston Street Building

When the McKim building first opened, it shared a city block with Harvard Medical School. That space is now the location of the library’s Boylston Street building, which opened in 1972 and doubled the size of the Central Library. Architect Philip Johnson drew inspiration from the McKim building for his design. The two buildings are of similar size and scale, and both are oriented around a central court, one exterior and one interior. Their exteriors are also made of the same Milford pink granite, though it is used in very different architectural styles.

The Boylston Street building underwent a major renovation that concluded in 2016 and transformed it into an open, dynamic space. The original Boylston Street building was made up of smaller rooms and divided from the surrounding neighborhood by tinted glass and a wall of granite pillars. Now, the first floor is open to the surrounding sidewalk and features a popular radio broadcast station.

Like the McKim building, the Boylston Street building required a unique foundation to be built atop landfill. The Boylston Street building sits on a thick concrete slab, and columns around the exterior and the central hall support a specially designed framework at the top of the building from which the lower floors are suspended.